OS Structure

Table of content

- OS service

- User & OS interface

- System calls

- System services

- linkers & loaders

- Why Application are OS specific

- OS design & implementation

- OS structure

- Building & Booting an OS

- OS debugging

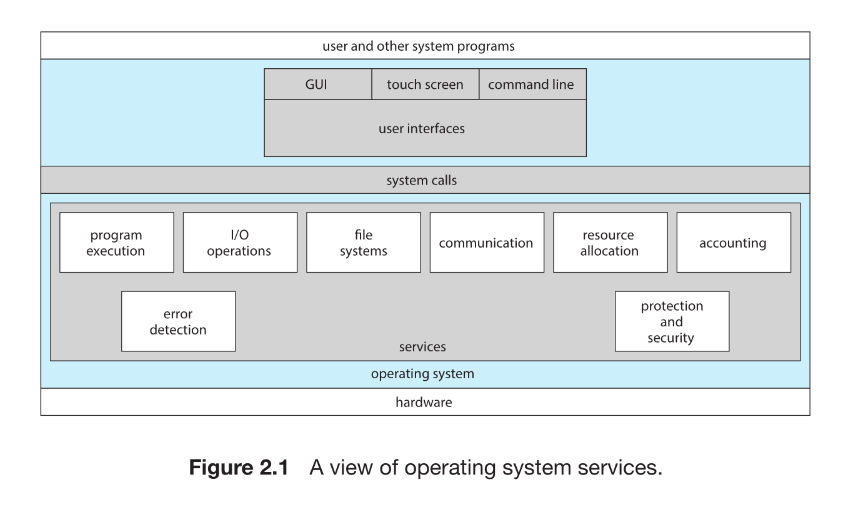

We can view an operating system from several vantage points One view focuses on the services that the system provides; another, on the interface that it makes available to users and programmers; a third, on its components and their interconnections.

OS service

An operating system provides an execution environment for programs and offers a set of services to users and applications. These services simplify programming tasks and ensure efficient and controlled use of system resources. OS services can be divided into user-oriented services and system-oriented services.

1. User-Oriented Services

a. User Interface (UI)

Operating systems provide mechanisms through which users interact with the system. Common forms include:

- Graphical User Interface (GUI): Window-based interface using mouse, keyboard, or touch.

- Touch-Screen Interfaces: Used in mobile devices, enabling gestures and on-screen buttons.

- Command-Line Interface (CLI): Text-based interface where commands are typed in a specific format.

Many systems support multiple UI types simultaneously.

b. Program Execution

The OS must:

- Load a program into memory

- Start its execution

- Provide mechanisms for normal or abnormal termination

c. I/O Operations

Programs often require input/output operations involving files or devices. Since direct device control by users is unsafe and inefficient, the OS:

- Provides system calls for device access

- Manages device communication on behalf of processes

d. File-System Manipulation

The OS offers services to:

- Create, delete, read, write, and search files and directories

- Manage permissions and access rights

- Support multiple file systems with differing performance and feature sets

e. Communications

Processes may exchange information:

- Within the same system or

- Across networked systems

Two main communication mechanisms:

- Shared Memory: Multiple processes read/write a common memory region.

- Message Passing: OS transfers structured messages between processes or over networks.

f. Error Detection

The OS continually checks for errors in:

- Hardware (memory faults, power issues)

- I/O devices (disk parity errors, network failures)

- User programs (illegal memory access, arithmetic overflow)

On detection, the OS takes appropriate action—terminate a process, return error codes, or halt the system.

2. System-Oriented Services

These services do not directly aid the user but maintain overall system efficiency and integrity.

a. Resource Allocation

When multiple processes execute concurrently, the OS must allocate:

- CPU time

- Main memory

- File storage

- I/O devices

Specialized algorithms (e.g., CPU scheduling) determine the best way to distribute resources.

b. Logging (Accounting)

The OS keeps records of:

- Resource usage

- Programs executed

- System statistics

These logs help with billing, auditing, tuning system performance, and planning upgrades.

c. Protection and Security

The OS safeguards system resources from unauthorized access.

Key aspects include:

- Protection: Ensures processes cannot interfere with each other or the OS.

-

Security: Prevents external and internal attacks through:

- User authentication (passwords, credentials)

- Access control to devices and files

- Monitoring and recording suspicious activity

A robust system enforces security at every layer—“a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.”

User & OS interfaces

Operating systems offer multiple ways for users to interact with system services. The three primary interface types are: (1) Command-Line Interface (CLI), (2) Graphical User Interface (GUI), and (3) Touch-Screen Interface.

Each interface type serves different user groups, environments, and device categories.

1. Command Interpreters (CLI)

Definition

A command interpreter—also called a shell—is a program that accepts and executes user commands.

Key Features

- Runs when the user logs in or when a process starts.

- Common shells in UNIX/Linux: bash, csh, ksh, etc.

- Allows commands for file manipulation (create, delete, execute, copy, list, etc.).

Two Implementation Approaches

-

Command-in-Interpreter:

- Interpreter contains built-in code for each command.

- Interpreter size grows with number of commands.

-

Command-as-Program (Used by UNIX/Linux):

- Interpreter locates and executes external programs.

-

Example:

rm file.txtloads and runs the program

rmwith argumentfile.txt. - Enables easy addition of new commands without modifying the shell.

2. Graphical User Interface (GUI)

Definition

A visually oriented interface using windows, icons, menus, and pointer devices (mouse or touch).

Characteristics

- Represents files, folders, and applications as icons.

- Common in macOS, Windows, Linux desktop environments.

- Origin: Early GUI research at Xerox PARC (1970s).

- Popularized by Apple Macintosh and later Microsoft Windows.

Examples

- macOS Aqua

- Windows GUI

- Linux desktop environments: KDE, GNOME

3. Touch-Screen Interface

Definition

An interface where users interact directly with the screen using gestures (tap, swipe, pinch).

Usage

- Standard for smartphones and tablets.

- On-screen virtual keyboards replace physical ones.

Examples

- iPhone and iPad (Springboard interface)

- Android devices

4. Choice of Interface

CLI vs GUI Preferences

-

CLI preferred by system administrators and power users because:

- Faster for many tasks

- Supports automation through shell scripts

- Some advanced system functions exist only in CLI

-

GUI preferred by most general users because:

- Easier to learn

- More intuitive for everyday tasks

Platform Differences

- Traditional UNIX/Linux: Primarily CLI, but GUIs available (KDE, GNOME).

- Windows: Mostly GUI; CLI used rarely by typical users.

- macOS: Offers both Aqua GUI and CLI (Terminal).

- Mobile (iOS/Android): Almost exclusively touch-based; CLIs exist but are rarely used.

OS Perspective

- Interface choice is largely independent of internal OS design.

- OS focuses on providing services to programs, not on dictating the UI style.

System calls

- System calls provide the interface between user programs and the operating system.

- Usually exposed as C/C++ functions; some require assembly for low-level hardware access.

- Allow programs to request OS services such as process creation, I/O, file operations, communication, and protection.

2. Example: File Copy Program (Conceptual Flow)

A simple copy program uses many system calls:

Input Gathering

- Write prompt to screen → system call

- Read input filename + output filename → system call

Opening/Creating Files

open()input file- Handle errors (file not found, permission denied)

create()output file; handle existing file cases

Copy Loop

read()from inputwrite()to output- Check for errors (EOF, device issues)

Termination

close()both files- Write completion message

- Normal process exit

→ Even simple programs involve dozens of system calls.

3. Application Programming Interface (API)

Purpose

- Programmers work through APIs (Windows API, POSIX API, Java API) instead of calling system calls directly.

- API functions internally invoke the appropriate OS system calls.

Benefits

- Portability: Same API works across OS versions.

- Simplicity: System calls are low-level; APIs make programming easier.

- Abstraction: Hides implementation details and system call numbers.

Example

- Windows

CreateProcess()→ internally triggers kernel callNtCreateProcess(). - POSIX

read()andwrite()map directly to UNIX/Linux system calls.

4. Role of the Run-Time Environment (RTE)

- RTE includes the language libraries, loaders, interpreters.

- Intercepts API calls and sends them to the system-call interface.

-

System-call interface:

- Maps each call to a system call number

- Looks up the function in a table

- Switches from user mode → kernel mode, executes call, returns result

5. How Parameters Are Passed to System Calls

Three standard techniques:

- Pass parameters in registers (fastest, limited by register count)

- Pass a memory block/table containing parameters and pass its address in a register

- Use the stack (push parameters → OS pops them)

Linux uses registers for ≤ 5 parameters, otherwise uses a memory block.

6. Types of System Calls

System calls fall into six categories:

6.1 Process Control

create process,terminate processload,executewait,signalget/set process attributesallocate/free memory

Used for: Program execution control, error handling, debugging.

Examples: fork(), exec(), exit(), wait()

6.2 File Management

create,deletefilesopen,closeread,write,repositionget/set file attributes

6.3 Device Management

requestdevice,releasedeviceread,write,repositionget/set device attributes- Attach/detach devices

Many OSes unify files and devices under a single interface.

6.4 Information Maintenance

get/set timeget/set system dataget/set process, file, device attributes- Memory dump & debugging support (

dump())

6.5 Communications

Two IPC models:

A. Message Passing

open connection,close connectionsend message,receive message- Needs address translation:

gethostid(),getpid()

Used with daemons, servers, and networked processes.

B. Shared Memory

shared_memory_create()shared_memory_attach()- Fastest communication method but needs synchronization.

6.6 Protection

- Controls access to system resources.

-

System calls include:

set permissions,get permissionsallow user,deny user

Essential for multi-user systems and networked environments.

7. Example OS Behavior

Single-tasking (Arduino)

- No OS; sketch runs directly.

- Boot loader loads program → only one program at a time.

Multitasking (FreeBSD)

-

Shell starts processes using:

fork()→ creates a new processexec()→ runs a new program in that process

- Processes run in foreground or background.

- Termination via

exit().

8. System Call Examples (Windows vs. UNIX)

| Function Area | Windows | UNIX/Linux |

|---|---|---|

| Process control | CreateProcess() |

fork() |

ExitProcess() |

exit() |

|

| File mgmt | CreateFile() |

open() |

ReadFile() |

read() |

|

| Device mgmt | SetConsoleMode() |

ioctl() |

| Info | GetCurrentProcessId() |

getpid() |

| Comm. | CreatePipe() |

pipe() |

| Protection | SetFileSecurity() |

chmod() |

System Service

1. Definition

- System services (system utilities) sit above the operating system and below application programs.

- Provide a convenient environment for program development and execution.

- Many are simple wrappers around system calls; others are complex standalone tools.

2. Categories of System Services

A. File Management

- Create, delete, copy, rename files and directories

- Print, list, and manipulate file system content

- Provide user-level access to file operations

B. Status Information

- Retrieve system status: date, time, available memory, disk space, number of users

- Provide performance data, logs, and debugging information

- Output may be text, file logs, GUI windows

- Some OSes include a registry for configuration storage

C. File Modification

- Text editors for creating and editing file contents

- Tools to search file contents and perform text transformations

D. Programming-Language Support

- Compilers, assemblers, interpreters (C, C++, Java, Python, etc.)

- Debuggers and related development tools

E. Program Loading and Execution

- Loaders: absolute, relocatable, linkers, overlay loaders

- Systems to execute programs after compilation

- Machine-level and high-level language debugging facilities

F. Communications

- Enable communication between processes, users, and systems

-

Support activities such as:

- Messaging between users

- Web browsing

- Remote login

- File transfers

G. Background Services

- System-program processes started at boot

- Some run once; others run continuously as services/subsystems/daemons

-

Examples:

- Network daemons (listen for connections)

- Scheduled task runners

- Error monitoring services

- Print servers

- Many OSes run dozens of daemons

- Used especially when tasks run in user context instead of kernel context

3. Application Programs Provided with OS

-

Most OS distributions include commonly used applications:

- Web browsers

- Word processors

- Text formatters

- Spreadsheets

- Databases

- Compilers

- Graphics/statistics tools

- Games

4. User’s View of the Operating System

- Users typically interact through system programs and application programs, not system calls.

-

The same OS services can appear differently under:

- GUI (e.g., macOS desktop)

- CLI (e.g., UNIX shell)

- Dual booting demonstrates differing interfaces using the same hardware (e.g., macOS vs Windows).

Linkers and Loaders

1. Where Programs Begin

-

Programs initially exist on disk as binary executable files Examples:

a.out,prog.exe. -

To run on a CPU, this binary must be:

- Loaded into memory

- Placed inside a process’s address space

- Scheduled on a CPU core

2. Full Pipeline: Compile → Link → Load → Execute

A. Compilation

- Source code → Object file

-

Object files are in relocatable format, meaning:

- They can be loaded into any memory address.

-

Hands-on example:

gcc -c main.cOutput:

main.o(relocatable object file)

B. Linking

-

Objective: Combine multiple object files + libraries → single executable

-

Linker resolves:

- Function calls across files

- Library references (

printf,sqrt, etc.) - Symbol addresses

-

Hands-on command:

gcc -o main main.o -lm-lm= link math library -

Output:

main(binary executable)

C. Loading (performed by OS loader)

- Loader places executable into the process’s address space.

-

Loader performs relocation:

- Assigns final addresses to code & data

- Fixes references to functions, global variables, library calls

Hands-on: How loading actually happens on UNIX

-

You type:

./main -

The shell calls:

fork()→ creates a new processexec("./main")→ replaces the child with your program

-

Loader loads the program into memory.

GUI equivalent

- Double-clicking an app internally triggers a similar exec-like loader call.

3. Dynamic Linking (DLLs / Shared Objects)

Most modern systems do NOT link all libraries into the executable.

Why dynamic linking?

- Saves memory

- Reduces executable size

- Loads library only if needed during runtime

Hands-on example (Linux shared libs)

- Executable does NOT contain math library code.

-

Instead, linker inserts relocation info:

- Loader will dynamically link libm.so if program calls its functions.

Windows equivalent

- Uses DLLs (Dynamic-Link Libraries)

Bonus: Shared libraries can be shared across processes

-

Memory-efficient because:

- OS maps the same library into multiple processes

- Code section is shared

- Only data sections are private

4. File Formats (Practical OS Concepts)

ELF (Executable and Linkable Format) – Linux / UNIX

-

Used by:

- Object files

- Executable files

- Shared libraries

-

Includes:

- Machine code

- Symbol tables (function names, variable references)

- Entry point (first instruction address)

Hands-on ELF inspection

file main.o # Shows "ELF relocatable"

file main # Shows "ELF executable"

readelf -h main # Detailed breakdown of ELF headers

PE (Portable Executable) – Windows

Equivalent format used for .exe and .dll.

Mach-O – macOS

Used for macOS and iOS programs.

5. Summary Diagram (Conceptual Flow)

Source Code (main.c)

|

| gcc -c main.c

v

Relocatable Object File (main.o)

|

| gcc -o main main.o -lm

v

Executable File (main)

|

| ./main → fork() → exec()

v

Loader loads program + performs relocation

|

v

Program running in memory → scheduled on CPU core

6. Key Hands-On Takeaways (Exam + Practical)

Compilation

- Use

gcc -c file.cto produce relocatable.ofiles.

Linking

- Use

gcc -o exec file.o -lmto link libraries.

Loading

- Happens automatically when calling

exec(). - Shell triggers

fork()thenexec().

Dynamic Linking

- Saves memory.

- Libraries loaded on demand.

- Shared across processes.

ELF Tools

file— identify file type.readelf— inspect ELF headers.

Why we have OS-specific Applications?

1. Core Reason

Applications compiled for one operating system cannot run on another because:

- Each OS provides its own system calls, binary formats, APIs, and ABIs.

- CPUs have different instruction sets, so binaries are architecture-specific.

2. How Apps Become Cross-Platform (Three Methods)

1. Interpreted Languages (Python, Ruby)

- Source code is interpreted line-by-line by an interpreter available on each OS.

- Interpreter translates instructions and calls OS-native system calls.

- Pros: Portability.

- Cons: Slower performance; limited feature access.

2. Virtual Machine–Based Languages (Java JVM)

- Program compiled to bytecode, then executed by a Virtual Machine (VM).

- The VM (part of language’s RTE) is ported to many OSes.

- Pros: Same bytecode runs anywhere the VM exists.

- Cons: Similar performance overhead and feature limitations as interpreters.

3. Using Standard APIs (e.g., POSIX)

- Program compiled separately for each OS using a common API standard.

- Requires porting + recompilation + testing for each operating system.

- Pros: High performance, native features.

- Cons: Time-consuming; must port every new version.

3. Why Cross-Platform Execution Is Still Hard

A. Different OS Binary Formats

- Linux/UNIX → ELF

- Windows → PE

- macOS → Mach-O Each format specifies:

- Header layout

- Code & data locations

- Loading rules

B. CPU Instruction Set Differences

- Example: x86 vs ARM A binary compiled for one cannot run on another.

C. System Call Differences

OSes differ in:

- System call names

- Call numbers

- Operand ordering

- How calls are invoked (trap instructions, software interrupts)

- Return values and error codes

Thus, even identical program logic cannot run without modification.

4. ABI (Application Binary Interface)

-

Defines binary-level rules for one OS on one architecture:

- Address width

- Parameter passing (stack/registers)

- Stack layout

- Binary library formats

- Data type sizes

ABIs help maintain compatibility within the same OS + CPU family, but do NOT solve cross-platform portability.

Example:

- ABI for ARMv8: executable works only on systems supporting that ABI.

5. Practical Implication

To run on multiple OSes and CPU architectures (e.g., Windows, macOS, Linux, Android, iOS), an application must be:

- Interpreted, or

- Run through a VM, or

- Recompiled and ported separately for each OS + CPU combination.

This explains the heavy engineering effort behind multi-platform applications like:

- Firefox

- Chrome

- VS Code

- Spotify

6. Final Insight

An app only runs if its binary, system calls, APIs, and ABI match the OS + CPU.

Otherwise, it cannot load or execute, even if the code itself is correct.

OS Design & Implementation

1. Design Goals

A. System-Level Context

Operating-system design depends on:

- Hardware platform

- System type: desktop/laptop, mobile, distributed, real-time, embedded

B. Two Categories of Requirements

1. User Goals

Users want:

- Easy-to-use, intuitive system

- Reliable and safe

- Fast and responsive

(Vague; not directly actionable for design.)

2. System Goals

Developers want:

- Easy to design, implement, maintain

- Flexible

- Reliable and error-free

- Efficient

(Also vague; require engineering interpretation.)

C. No Universal Design

Different requirements → Different OS designs Examples:

- VxWorks (embedded, real-time)

- Windows Server (enterprise, multiaccess, general-purpose)

OS design is a creative engineering task, guided by software engineering principles.

2. Mechanisms vs Policies (Critical OS Design Principle)

Mechanism

How a function is performed. Example:

- Timer interrupt → mechanism for CPU protection

Policy

What should be done. Example:

- How long each user gets CPU time → policy

Why the Separation Matters

- Policies change over time and across environments

- Mechanisms should remain stable

- Enables flexibility and reusability

- Changing a policy should not require rewriting mechanisms

Example: Priority mechanism can support:

- Giving priority to I/O-bound tasks

- OR giving priority to CPU-bound tasks (Policy decides; mechanism stays same.)

3. Mechanism/Policy in Real Systems

Microkernel Approach

- Very small kernel

- Mostly mechanism; policies added via modules or user programs

- Highly flexible, customizable

Monolithic Commercial Systems (Windows, macOS)

- Mechanisms + policies tightly integrated

- Ensures uniform behavior and UI across all devices

- Less flexibility for system modification

Open Source Systems (Linux)

- Mechanism available; policies modifiable

- Anyone can replace core components (e.g., CPU scheduler)

4. OS Implementation

A. Languages Used

Modern OS implementations use:

- C and C++ for most kernel and system code

- Assembly only for low-level hardware handling

- Higher-level languages for frameworks and libraries

Example: Android

- Kernel → C + Assembly

- System libraries → C / C++

- Application framework → Java

B. Benefits of Using Higher-Level Languages

- Faster development

- More compact and maintainable code

- Easier debugging

- Easier portability across hardware

- Compiler improvements automatically improve OS performance

C. Potential Disadvantages

- Slightly lower speed than pure assembly

- Slightly higher memory overhead → Not significant today due to powerful CPUs and optimizing compilers

D. What Actually Improves OS Performance

Major gains come from:

- Better algorithms

- Better data structures

Not from micro-optimizing assembly code

Performance-critical OS components:

- Interrupt handlers

- I/O manager

- Memory manager

- CPU scheduler

These are optimized after correctness is achieved.

5. Practical Engineering Insight

- Write OS in a high-level language first

- Ensure correctness

- Identify bottlenecks with profiling

- Rewrite only the critical hot paths in optimized C or assembly

OS structure

1. Why OS Structure Matters

-

Modern OSes are large, complex, and must be:

- Easy to modify

- Reliable

- Maintainable

-

Solution → Break the OS into modules/components with clear interfaces (similar to decomposing a program into functions).

2. Monolithic Structure

Definition

- Entire OS kernel runs in one large binary within one address space.

Characteristics

- All core services (file system, scheduling, memory management, device drivers) run in kernel mode.

-

Very fast because:

- No message passing between components

- System calls are direct and lightweight

Examples

- Original UNIX

- Linux

- Windows (modern versions adopt monolithic + modular aspects)

Pros

- High performance

- Low overhead for system calls & internal communication

Cons

- Hard to maintain

- Hard to extend safely

- A bug in one part can crash the entire system

3. Layered Structure

Idea

-

OS divided into a hierarchy of layers:

- Layer 0 → hardware

- Layer N → user interface

Properties

- Each layer uses only lower layers

- Higher layers do not need to know internal implementation of lower layers

Benefits

- Easy to debug (errors are isolated by layer)

- Clean modularity & abstraction

- Easier verification

Drawbacks

- Performance overhead: multiple layers to cross for a simple operation

- Hard to define perfect layers

Used in

- TCP/IP networking model

- Some OS components (but pure layering is rare)

4. Microkernel Architecture

Idea

- Move most OS services to user space

-

Keep kernel minimal:

- Low-level memory management

- Basic scheduling

- IPC mechanisms

Communication

- All interactions occur through message passing via the microkernel.

Benefits

- Very secure (fault isolation)

- Very modular (easy to add services)

- Easier to port across architectures

Cons

- Performance overhead: copying messages between processes + context switching

- Historically slower than monolithic systems

Examples

- Mach (CMU)

- Darwin (macOS/iOS) → Mach microkernel + BSD kernel

- QNX (real-time embedded OS)

Real-world adjustments

- macOS puts Mach + BSD + drivers in one address space to reduce message-copy overhead → Hybrid microkernel

5. Modular Kernel (Loadable Kernel Modules)

Definition

- Kernel core + additional features loaded as modules at boot or runtime.

Properties

- Supports dynamic extension without recompiling the kernel

- Modules can call each other (not strictly layered)

- Faster than microkernels because no message passing

Advantages

- Flexibility + performance

- Easy to add device drivers, file systems, network stacks

Examples

- Linux (device drivers, file systems, networking)

- macOS / BSD variants

- Windows (uses loadable modules as well)

Hands-on relevance

- Adding USB driver dynamically

- Loading file system modules (e.g., ext4, NTFS)

- Kernel experiments without rebooting system

6. Hybrid Systems

Reality

-

Most real OSes mix approaches:

- Monolithic performance

- Microkernel modularity

- Layering for structure

Examples

- Linux → monolithic + modular

- Windows → monolithic + microkernel-like subsystems

- macOS/iOS → hybrid (Mach + BSD + I/O Kit in same address space)

7. Case Studies

A. macOS and iOS Architecture

Layers

-

User Experience Layer

- macOS → Aqua GUI

- iOS → Springboard (touch-based)

-

Application Frameworks

- Cocoa (macOS)

- Cocoa Touch (iOS) → supports touch, sensors, cameras

-

Core Frameworks

- QuickTime, OpenGL, Metal, media services

-

Kernel Environment (Darwin)

- Mach microkernel

- BSD kernel (POSIX APIs)

- I/O Kit + Kernel Extensions (kexts)

macOS vs iOS

- macOS for Intel (historically) / ARM Macs now

- iOS for ARM-based mobile devices

-

iOS has:

- Stricter security

- Aggressive memory + power management

- Restricted libc/POSIX access

B. Android Architecture

Layers

- Applications (Java/Kotlin)

-

ART VM (Android Runtime)

- AOT compilation → converts .dex → native code

- More efficient for mobile devices

-

Android Frameworks

- UI, media, sensors, telephony, activities, services

-

Native Libraries

- WebKit (browser engine)

- SQLite

- SSL

- Surface Manager

-

HAL (Hardware Abstraction Layer)

- Provides uniform hardware interface

- Enables portability across phones/tablets

-

Linux Kernel (modified)

- Binder IPC

- Power & memory management changes

- Drivers for mobile hardware

Bionic libc

- Smaller, faster than glibc

- Designed for mobile CPUs

- Avoids GPL dependencies

8. Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL)

Purpose

- Run native Linux ELF binaries on Windows 10/11

How it works

- User starts

bash.exe -

WSL creates Linux-like environment using:

- LXCore

- LXSS

-

Linux system calls translated to:

- Equivalent Windows system calls (direct mapping when possible)

- Or partial emulation (e.g., fork requires special handling)

Key concept

- Linux binaries run inside Pico processes on Windows

- Not virtualization → system call translation layer

Building & Booting an OS

1. OS Generation (Building an Operating System)

Why OS generation is needed

- Systems may come without an OS or with an OS you wish to replace.

- OS must often be configured for specific hardware (CPU, devices, drivers).

1.1 Steps to Build an OS from Scratch

- Write or obtain OS source code

-

Configure the OS for the target hardware

- Feature selection

- Drivers

- Memory/disk parameters

- Stored in a configuration file

- Compile the OS

- Install the OS

- Boot the machine into the new OS

1.2 Configuration Approaches

Three primary approaches differ in tailoring vs. generality:

A. Compile-Time Customization (Most rigid)

- Configuration file modifies source

- OS fully recompiled → system build

- Best for embedded systems (fixed hardware)

B. Precompiled Module Selection (Common today)

- Choose required modules from libraries (e.g., only needed drivers)

- Faster than recompiling the whole kernel

- OS still somewhat generic

C. Fully Modular (Most dynamic)

- Decisions made at runtime

- Uses dynamic modules / plug-ins

- Example → Linux Loadable Kernel Modules (LKMs)

2. Hands-on Example: Building Linux Kernel

Steps to compile and install a custom Linux kernel:

-

Download source

- From:

https://kernel.org

- From:

-

Configure kernel

- Command:

make menuconfig - Generates

.configfile

- Command:

-

Compile kernel

make- Produces

vmlinuz(compressed kernel image)

-

Compile modules

make modules

-

Install modules

make modules_install

-

Install kernel

make install- Updates boot loader automatically (e.g., GRUB)

After reboot → system runs the new kernel

2.1 Installing Linux via Virtual Machine

Two practical options:

A. Build VM from scratch

- Boot VM using Linux ISO

- Run installer (no kernel compilation needed)

B. Use VM Appliance (Pre-built VM image)

- Download ready-made VM

- Import into VirtualBox/VMware

3. System Boot Process (How a Computer Starts an OS)

High-Level Boot Steps

- Bootstrap/boot loader starts

- Kernel is located and loaded into memory

- Kernel initializes hardware

- Root filesystem is mounted

3.1 BIOS vs UEFI Booting

BIOS (Older, multistage)

- BIOS loads a small boot loader from boot block

- Boot block loads full bootstrap loader

- Bootstrap loads OS kernel

UEFI (Modern, single-stage)

- Faster startup

- Supports large disks, 64-bit systems

- Acts as a full boot manager

3.2 What Boot Loader Does

Typical responsibilities:

- Hardware diagnostics

- Initialize CPU registers, controllers

- Load kernel into memory

- Mount initial filesystem

- Start OS initialization process

3.3 GRUB (Linux Boot Loader)

- Open-source, widely used in UNIX/Linux

- Editable boot-time configuration

- Allows selecting different kernels

Example /proc/cmdline parameters

BOOT_IMAGE=/boot/vmlinuz-4.4.0-59-generic

root=UUID=5f2e2232-4e47-4fe8-ae94-45ea749a5c92

BOOT_IMAGE→ kernel file to loadroot→ root filesystem location (UUID)

3.4 initramfs (Initial RAM Filesystem)

Purpose

- Temporary filesystem created by boot loader

- Contains essential drivers & modules required to access the real root filesystem

Linux Boot Flow

- Load compressed kernel

- Load

initramfs - Kernel installs required drivers

- Switch root from

initramfs→ disk root filesystem - Start systemd (PID 1)

- Services start

- Show login prompt

3.5 Android Boot Process

Android uses its own boot loader (often LK — Little Kernel).

Key Android differences

- Kernel is Linux-based but does not use GRUB

initramfsbecomes permanent root filesystem-

After boot:

- Kernel starts Android’s

init - Creates services

- Loads home screen (Launcher)

- Kernel starts Android’s

4. Recovery / Single-User Mode

Most OS boot loaders support:

- Booting into recovery mode

- Filesystem repair

- Fixing kernel issues

- Reinstalling or repairing OS installations

Supported by:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

- Android & iOS (via specialized recovery tools)

✔ Summary (For Exam / Revision)

- OS building involves config → compile → install → boot.

- Kernel configuration ranges from fully compiled to modular runtime loading.

- Linux kernel build uses

make,.config, and dynamic modules. - Boot process requires a bootstrap loader (BIOS/UEFI → GRUB → kernel).

- initramfs provides a temporary environment until real root filesystem loads.

- Android boot uses LK, keeps initramfs permanently.

- Boot loaders provide recovery and OS selection capabilities.

OS Debugging

1. Debugging in Operating Systems — Core Ideas

Debugging = finding + fixing errors in software or OS kernel. Includes:

- Failure debugging (crashes, improper behavior)

- Performance tuning (removing bottlenecks)

Hardware debugging is excluded.

2. Failure Analysis

2.1 User-Level Process Failure

When a user process fails:

- OS writes error details to a log file

- OS may capture a core dump (snapshot of process memory)

- A debugger (e.g.,

gdb) inspects core + running program

⚙ Hands-on Example (Linux) View core dump:

gdb ./program core

2.2 Kernel Failure

Kernel failures = crashes (panic in Linux, BSOD in Windows)

Challenges:

- Kernel cannot safely write to filesystem during a crisis (filesystem may be unstable)

-

Solution:

- Save crash dump to a non-filesystem disk region

- On reboot, a recovery process moves dump → file for analysis

⚙ Practical Insight Crash dump handling must not rely on filesystem drivers, since those drivers may be the cause of failure.

3. Performance Monitoring & Tuning

Goal: Identify bottlenecks & fix them.

Two monitoring approaches:

- Counters (state snapshot)

- Tracing (event-by-event sequence)

4. Counter-Based Monitoring Tools

4.1 Linux Per-Process Tools

| Tool | Purpose |

|---|---|

ps |

Reports info about specific processes |

top |

Live CPU, memory, process stats |

4.2 Linux System-Wide Tools

| Tool | Purpose |

|---|---|

vmstat |

Memory usage & paging statistics |

netstat |

Network interface stats |

iostat |

Disk I/O usage stats |

/proc Filesystem (Key Hands-on Detail)

Linux exposes counters via /proc pseudo-filesystem.

Examples:

cat /proc/cpuinfo # CPU details

cat /proc/meminfo # Memory usage

cat /proc/2155/status # Per-process info for PID 2155

5. Windows Performance Tools

Windows Task Manager

Shows:

- CPU usage

- Memory usage

- Per-process runtime stats

- Networking throughput

6. Tracing Tools (Event-Centric Analysis)

Tracing = capturing every step of system activity (system calls, IO events).

6.1 Linux Per-Process Tracing

| Tool | Purpose |

|---|---|

strace |

Trace system calls used by a process |

gdb |

Source-level step debugging |

Example:

strace ls

strace -p 1225 # attach to running process

6.2 Linux System-Wide Tracing

| Tool | Purpose |

|---|---|

perf |

CPU profiling, kernel events, performance counters |

tcpdump |

Capture network packets |

Example:

sudo perf top

sudo tcpdump -i eth0

7. BCC (BPF Compiler Collection) — Modern Kernel Tracing

BCC = advanced toolkit built on eBPF (extended Berkeley Packet Filter) Purpose:

- Dynamically instrument kernel + user-level code

- Low overhead, safe, verified execution

How BCC/Ebpf Works

- Write tracing logic in Python

- Embed C code that compiles into eBPF instructions

-

eBPF code inserted into the running kernel using:

- kprobes / uprobes (function entry instrumentation)

- tracepoints (predefined kernel events)

-

eBPF verifier checks:

- safety

- no infinite loops

- minimal performance impact

7.1 Hands-on BCC Examples

Disk I/O tracing

./disksnoop.py

Sample Output:

TIME(s) T BYTES LAT(ms)

1946.29 R 8 0.27

1946.33 R 8 0.26

1948.34 R 8192 0.96

1950.43 W 4096 0.56

Interpretation:

- R/W = Read/Write

- BYTES = I/O size

- LAT = latency per operation

Tracing open() calls for a specific process

./opensnoop -p 1225

Tracks all open system calls made by PID 1225.

8. Kernighan’s Law (Classic Debugging Insight)

“Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place.”

Meaning: write simple, readable code so debugging remains possible.

✔ Summary Table (One-Page Revision)

| Area | Key Concepts | Hands-on Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Failure Analysis | Core dump, kernel crash dump | gdb, OS crash logs |

| Counters | Snapshot metrics | ps, top, vmstat, netstat, /proc |

| Tracing | Step-by-step activity | strace, perf, tcpdump |

| Modern Tracing | Dynamic kernel instrumentation | BCC (eBPF) tools |

| Kernel Debug Challenges | No filesystem reliability during crash | Crash dump to raw disk partition |