OS Intro

Table of Content

- what OS do

- Computer system organization

- Computer system architecture

- OS operations

- Resource management

- Security and protection

- Virtualization

- Distributed system

- Kernel Datastructure

- Computing environment

- Free and Open-source OS

What OS do ?

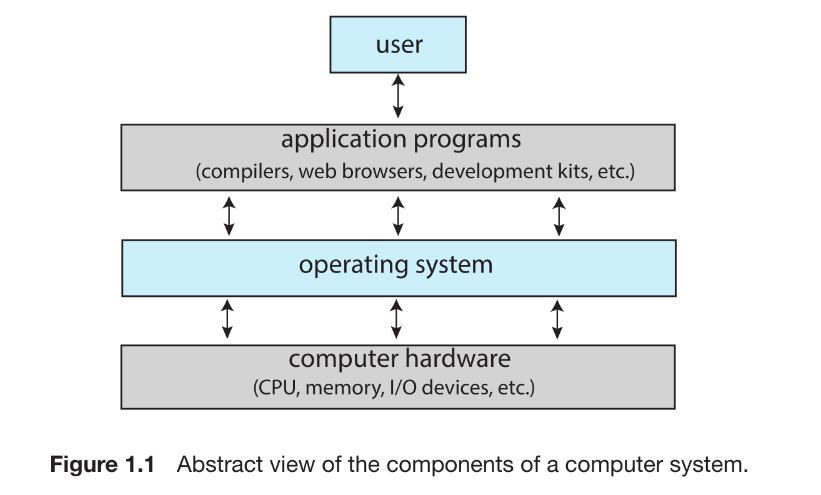

A computer system can be divided roughly into 4 components:

- the hardware : the central processing unit (CPU), the memory, and the input/output (I/O) devices—provides the basic computing resources for the system

- the OS :

- user view: It performs no useful function by itself. It simply provides an environment within which other programs can do useful work.

- system view: an operating system as a resource allocator. A computer system has many resources that may be required to solve a problem: CPU time, memory space, storage space, I/O devices, and so on. The operating system acts as the manager of these resources.

- the application programs : define the ways in which these hardware-resources are used to solve users’ computing problems

- a user

To be precise OS is the combination of (Hardware, Kernel, syscalls, system libraries, Shell, Apps). But since kernel is the core component of the OS. So, the term “OS” & “kernel” used interchangably.src

the operating system is the one program running at all times on the computer—usually called the kernel. Along with the kernel, there are two other types of programs:

- system programs: which are associated with the OS but are not necessarily part of the kernel. Eg: systemd, DWM.exe

- application programs: which include all programs not associated with the operation of the system. Eg: chrome.exe

Mobile operating systems often include not only a core kernel but also middleware—a set of software frameworks that provide additionalservices to application developers.

Computer System Organization

A computer system consists of one or more CPUs and a number of device controllers connected through a common bus that provides access between components and shared memory

A device controller maintains some local buffer storage and a set of special-purpose registers. The device controller is responsible for moving the data between the peripheral devices that it controls and its local buffer storage.

Typically, operating systems have a device driver for each device controller. This device driver understands the device controller and provides the rest of the operating system with a uniform interface to the device. The CPU and the device controllers can execute in parallel, competing for memory cycles. To ensure orderly access to the shared memory, a memory controller synchronizes access to the memory.

device driver = software that speaks controller language

device controller = harware(chip) controls the physical device found either on motherboard or device.

device = pendrive/wifi mouse.

Interrupt

- Hardware may trigger an interrupt at any time by sending a signal to the CPU, usually by way of the system bus.

- When the CPU is interrupted, it stops what it is doing and immediately transfers execution to a fixed location. The fixed location usually contains the starting address where the service routine for the interrupt is located.The interrupt service routine executes; on completion, the CPU resumes the interrupted computation.

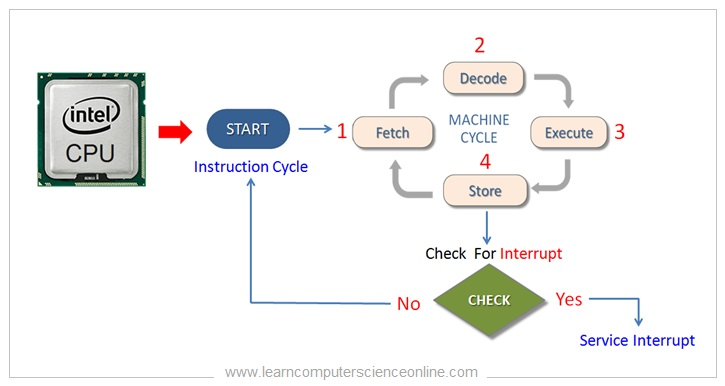

- implementation : The CPU hardware has a wire called the interrupt-request line that the CPU senses after executing every instruction

ADD X, YorMOV X, Y. When the CPU detects that a controller has asserted a signal on the interrupt-request line, it reads the interrupt number and jumps to the interrupt-handler routine by using that interrupt number as an index into the interrupt vector. It then starts execution at the address associated with that index. The interrupt handler saves any state it will be changing during its operation, determines the cause of the interrupt, performs the necessary processing, performs a state restore, and executes a return from interrupt instruction to return the CPU to the execution state prior to the interrupt.

CPU cycle: The smallest unit of time. The system clock “ticks,” and electricity moves one step through the circuit. (TTC: 1 ns)

Interrupt cycle: A complete, atomic action. (TTC: ~5 ns)

User command: composed of thousand or million of Interrupt cycle. (TTC : ms)

- In a modern operating system, however, we need more sophisticated interrupt-handling features.

- We need the ability to defer interrupt handling during critical processing.

- We need an efficient way to dispatch to the proper interrupt handler for a device.

- We need multilevel interrupts, so that the operating system can distinguish between high and low-priority interrupts and can respond with the appropriate degree of urgency.

-

Most CPUs have two interrupt request lines: One is the nonmaskable interrupt: which is reserved for events such as unrecoverable memory errors. The second interrupt line is maskable: it can be turned off by the CPU before the execution of critical instruction sequences that must not be interrupted. The maskable interrupt is used by device controllers to request service

-

A PC connects to \(n\) different devices (WiFi, Bluetooth, Keyboard, Mouse, etc.). If the CPU used Polling: checking every single device after every instruction cycle to see if it needs attention. The system would be incredibly slow. To solve this, we use an interrupt vector. This allows the CPU to identify exactly which device sent the interrupt and jump directly to that device’s specific code. However, modern PCs have more devices than available vector slots. To fix this limitation, we use interrupt chaining. In this method, a group of devices shares a single vector slot. When an interrupt occurs on that shared line, the CPU checks the devices in that group one by one to find out which one sent the signal.

- The interrupt mechanism also implements a system of interrupt priority levels. These levels enable the CPU to defer the handling of low-priority interrupts without masking all interrupts and makes it possible for a high-priority interrupt to preempt the execution of a low-priority interrupt.

Storage Structure

- Why Programs Need Memory?

- The CPU can execute instructions only from memory.

- Therefore, programs must first be loaded into main memory (RAM) before they run.

- Main Memory (RAM)

- Usually implemented using DRAM (Dynamic RAM).

- Volatile: loses its data when power is removed.

- General-purpose programs run from RAM because it is fast and rewritable.

- Bootstrap and Firmware

- When the computer powers on, the bootstrap program runs first and loads the OS.

- Bootstrap cannot be kept in RAM (because RAM is volatile).

- Stored in non-volatile firmware, usually:

- EEPROM (Electrically Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory)

- Other firmware chips

- Firmware:

- Non-volatile

- Very infrequently modified

- Slower than RAM

- Stores static data such as serial numbers, hardware info.

- Basic Storage Definitions

- Bit : Smallest storage unit; value = 0 or 1.

- Byte (8 bits) : Smallest convenient unit for CPU load/store operations.

-

Word : Architecture’s native data size (e.g., 64-bit word = 8 bytes).

- Many operations execute in word-size chunks.

- Storage Size Notation

- KB = 1,024 bytes

- MB = 1,024² bytes

- GB = 1,024³ bytes

- TB = 1,024⁴ bytes

- PB = 1,024⁵ bytes

- Manufacturers often round to 10³ units (1 MB = 1M bytes).

- Networking uses bits, not bytes.

- Memory Addressing and CPU Interaction

- All memory is an array of bytes, each with a unique address.

- Interaction happens via:

- load → memory → CPU register

- store → CPU register → memory

CPU automatically loads instructions from the address in the Program Counter (PC).

- Von Neumann Instruction Cycle

- Fetch instruction from memory → instruction register.

- Decode instruction.

- Fetch operands from memory (if needed).

- Execute instruction.

- Store results back to memory (if needed).

Memory sees only addresses; it does not know whether an address is for data or instructions.

- Limitations of Main Memory

- Too small to hold all programs/data permanently.

- Volatile : contents lost on power-off. Hence, computers need secondary storage.

- Secondary Storage

- Provides large, permanent data storage.

- Common types:

- HDDs (mechanical)

- NVM devices (e.g., SSD, flash)

- Characteristics:

- Slower than main memory.

- Used to store programs and data long-term.

- Programs are loaded into RAM before execution.

- Tertiary Storage

- Very slow, very large.

- Used mainly for backup/archive (e.g., magnetic tape, optical disks).

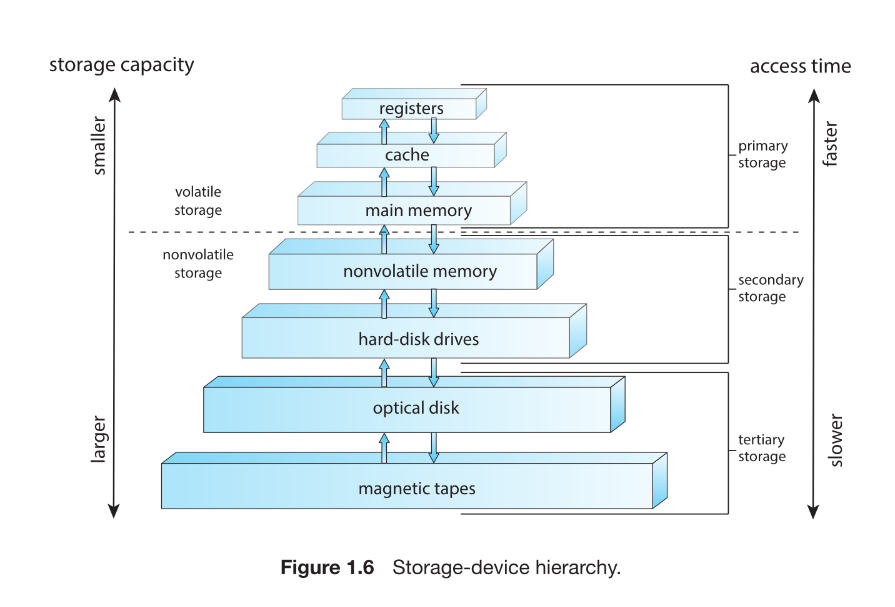

- Storage Hierarchy

- Key principle:

- Closer to CPU : smaller, faster, more expensive.

- Farther from CPU : larger, slower, cheaper.

- Key principle:

- Volatile vs Non-Volatile Storage

- Volatile (Memory) : Loses contents when power is removed.

- Includes: Registers, Cache, DRAM main memory

- Non-Volatile (NVS) : Retains data without power.

- Two categories:

- Mechanical Storage: HDDs, Optical disks, Magnetic tape

- Characteristics:

- Cheaper per byte

- Larger capacity

- Slower

- Characteristics:

- Electrical Storage (NVM): Flash, SSD, FRAM, NRAM

- Characteristics:

- Faster

- Smaller

- More expensive

- Characteristics:

- Mechanical Storage: HDDs, Optical disks, Magnetic tape

- Storage System Design Considerations

- A good system must balance:

- Speed

- Capacity

- Cost

- Volatility

Often includes caches to bridge gaps between fast CPU and slower memory/storage.

- A good system must balance:

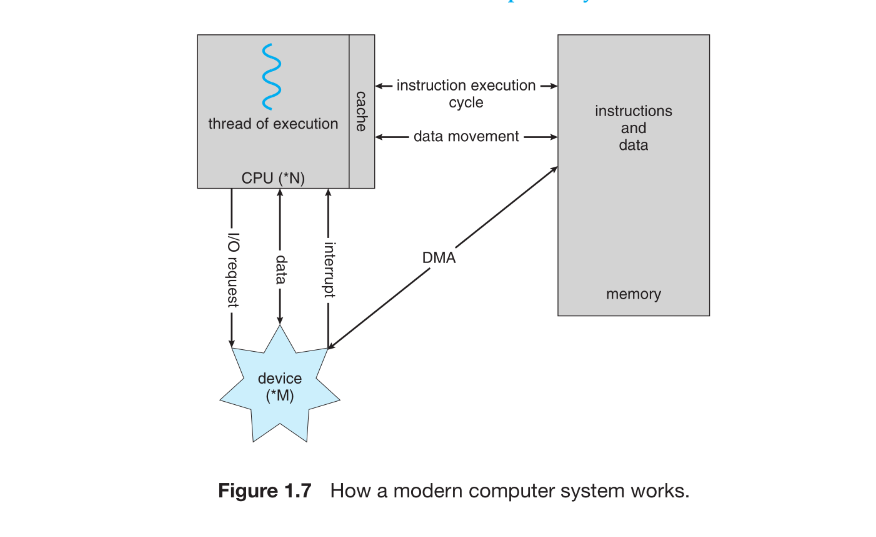

I/O Structure

- A major part of OS code handles I/O management because I/O impacts system performance and reliability, and devices vary widely.

- Traditional systems use a common system bus for communication between CPU, memory, and devices.

- Interrupt-driven I/O is suitable for small data transfers, but becomes inefficient for large transfers due to one interrupt per byte.

- Direct Memory Access (DMA) is used for high-volume I/O to reduce CPU overhead.

- In DMA, the OS sets up buffers, pointers, counters, and the device controller transfers a whole block directly between the device and main memory.

- DMA generates only one interrupt per block, signaling completion.

- DMA frees the CPU to do other work during data transfer.

- Bus architecture causes components to compete for bandwidth.

- High-end systems use switch-based architecture, allowing multiple simultaneous transfers, making DMA even more effective.

- Figure 1.7: CPU executes instructions, memory stores data, devices send interrupts, DMA moves data, all connected via bus or switch.

Computer System Architecture

- Systems are classified based on the number of general-purpose processors.

- Categories: Single-processor systems, Multiprocessor systems Clustered systems.

2. Single-Processor Systems

- Contains one general-purpose CPU with one core.

- May include special-purpose processors (disk controller, keyboard processor, graphics controller).

- Special-purpose processors:

- Run limited instruction sets.

- Do not execute user processes.

- Sometimes managed by OS; sometimes autonomous.

- System remains “single-processor” as long as there is one general-purpose CPU.Very few modern systems are truly single-processor anymore.

3. Multiprocessor Systems

- Two or more processors (traditionally one core each).

- Processors share:

- System bus

- Memory

- I/O devices

- Advantage: Increased throughput (more work in less time).

- Speed-up < N due to:

- Synchronization and coordination overhead.

-

Contention for shared resources.

3.1 Symmetric Multiprocessing (SMP)

- Each CPU is a peer and can execute:

- User processes

- OS kernel code

- Each CPU has:

- Its own registers

- Its own local cache (L1)

- All CPUs share the same physical memory.

- Benefits:

- Can run N processes on N CPUs simultaneously.

- Dynamic sharing of resources reduces load imbalance.

- Need careful OS design to share data structures safely.

3.2 Multicore Systems

- Multiple cores on a single chip.

- Faster on-chip communication vs. between physical chips.

- Lower power consumption vs. multiple single-core processors.

- Typical design:

- Per-core L1 cache

- Shared L2 cache

- OS sees each core as a separate logical CPU.

- Requires OS and application support for parallelism.

- Each CPU is a peer and can execute:

4. NUMA (Non-Uniform Memory Access) Systems

- Each CPU (or group of CPUs) has its own local memory.

- CPUs connected via a system interconnect; share one address space.

- Advantages:

- Local memory access is fast.

- Reduces bus contention = better scalability.

- Disadvantage:

- Slower access to remote memory; increases latency.

- OS must perform NUMA-aware scheduling and memory placement.

5. Blade Servers

- Multiple processor boards (“blades”) within a single chassis.

- Each blade:

- Boots independently

- Runs its own OS

- Some blades are multiprocessors → clusters of multiprocessors.

- Essentially: multiple independent computer systems packaged together.

6. Clustered Systems

- Two or more independent computer systems (nodes), typically multicore, linked together.

- Nodes share:

- Storage

- A LAN or fast interconnect (e.g., InfiniBand)

- Considered loosely coupled systems.

- 6.1 Purpose of Clustering

- High availability:

- If one node fails, another takes over ownership of storage and restarts applications.

- Users experience minimal downtime.

- Provides graceful degradation (performance reduces proportionally to surviving hardware).

- Fault-tolerant clusters survive the failure of any one component.

- 6.2 Clustering Models

- Asymmetric Clustering

- One active node + one hot-standby node.

- Standby only monitors active node; takes over on failure.

- Symmetric Clustering

- All nodes run applications and monitor one another.

- More efficient use of hardware.

- Asymmetric Clustering

- 6.3 Clusters for High-Performance Computing (HPC)

- All nodes cooperate to run parallel workloads.

- Uses parallelization:

- Application is divided into tasks running on separate cores/nodes.

- Results are combined to produce the final output.

- 6.4 Parallel Clusters

- Multiple hosts access the same shared storage.

- Requires:

- Specialized OS/application versions

- Distributed Lock Manager (DLM) for safe concurrent access

- 6.5 Modern Cluster Trends

- Clusters may include thousands of nodes.

- Nodes may be geographically distant.

- Enabled by storage-area networks (SANs):

- Applications and data stored centrally.

- Any node can take over if another fails.

- Greatly improves scalability and reliability.

CPU: Hardware that executes instructions.

Processor: A physical chip containing one or more CPUs/cores.

Core: Basic computational unit inside a CPU.

Multicore: Single CPU with multiple cores. (1 man with 10 hands doing 5 different task at same time)

Multiprocessor: System with multiple physical processors. (5 man doing 5 different task at same time)

NUMA : A scalable version of multiprocessor systems.

OS Operations

-

An operating system provides the environment in which application programs run, and although operating systems differ internally, they share several fundamental responsibilities. When a computer is powered on or rebooted, it must begin execution with a simple initial program known as the bootstrap program. This bootstrap program is stored in firmware and is responsible for initializing CPU registers, device controllers, and memory. It then locates the operating-system kernel, loads it into memory, and transfers control to it.

-

Once the kernel begins executing, it starts system programs that become long-running background processes, or daemons. On Linux, the first such daemon is systemd, which subsequently launches many other system services. After the boot sequence completes, the system remains idle until an event occurs. Most events are signaled by hardware interrupts, although software-generated interrupts, called traps or exceptions, also occur. Traps may arise due to errors such as division by zero or invalid memory access, or they may be deliberately generated by user programs through system calls that request operating-system services.

-

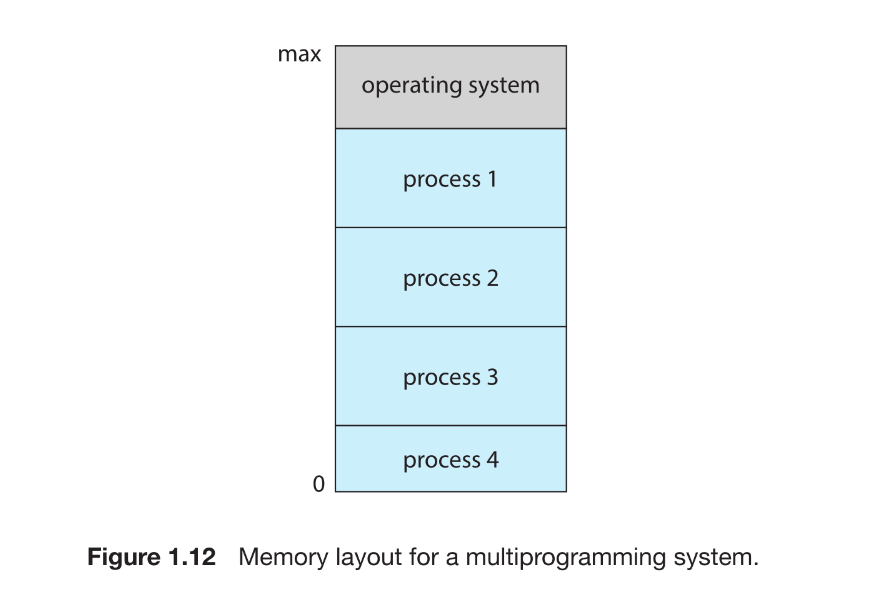

A fundamental goal of operating systems is to improve CPU utilization by enabling multiple programs to reside in memory and execute concurrently. This technique, known as multiprogramming, ensures that whenever one process must wait for I/O, another can be scheduled on the CPU. Multitasking extends this idea by switching among processes rapidly to provide interactive response times, especially important because human input devices operate far more slowly than CPUs. Supporting multiple simultaneously executing processes requires the operating system to manage memory, schedule CPU time, provide file-system access, protect resources, synchronize processes, and prevent or recover from deadlocks.

-

Because the operating system must remain protected from user programs, modern computers provide dual-mode operation. Hardware maintains a mode bit that distinguishes between user mode, where application code runs, and kernel mode, where the operating system executes privileged instructions. The system boots in kernel mode, and when a user program issues a system call or a trap or interrupt occurs, the hardware switches automatically to kernel mode so the OS can handle the request safely. Privileged operations—such as performing I/O, managing interrupts, or modifying the timer—may only be executed in kernel mode. Attempting to perform such operations in user mode results in a trap to the operating system, which typically terminates the offending process.

-

System calls represent the controlled mechanism through which user programs request OS services. Regardless of the processor architecture, executing a system call transfers control to a predefined OS routine via the interrupt vector, switches the CPU into kernel mode, and allows the OS to validate parameters, perform the requested operation, and return control to the user program.

-

To ensure the operating system periodically regains control from user processes, systems employ a hardware timer. The operating system configures this timer before relinquishing the CPU to user code. When the timer expires, it generates an interrupt that returns control to the OS, preventing any user program from monopolizing the CPU. In Linux, the frequency of timer interrupts is set by the configuration parameter HZ, and the kernel variable jiffies counts how many timer interrupts have occurred since boot. Because modifying the timer determines when control returns to the OS, timer instructions are privileged and may only be executed in kernel mode.

Resource Management

An operating system functions fundamentally as a resource manager, responsible for managing the CPU, main memory, file-storage space, and I/O devices. Each major subsystem of the OS handles a particular class of resources and ensures that programs can execute efficiently, safely, and concurrently.

Process Management

A program becomes meaningful only when its instructions are executed by the CPU. A program in execution is called a process, and it represents an active entity that consumes system resources such as CPU time, memory, files, and I/O devices. Processes may receive initialization data, such as when a web browser process is started with a specific URL. When a process completes, the operating system reclaims all reusable resources assigned to it. It is important to distinguish that a program is a passive collection of instructions stored on disk, whereas a process is an active execution context.

A single-threaded process has one program counter that tracks the next instruction to execute, ensuring sequential execution. Multiple processes may correspond to the same program but represent distinct execution sequences. A multithreaded process, on the other hand, contains multiple threads, each with its own program counter. The operating system maintains a collection of processes, some belonging to the OS itself and others belonging to users, all potentially executing concurrently. OS responsibilities in process management include creating and deleting processes, scheduling them on CPUs, suspending and resuming execution, and providing mechanisms for synchronization and interprocess communication. These topics form the foundation of Chapters 3 through 7.

Memory Management

Main memory is a central component of computer operation. It is a large array of individually addressable bytes that can be accessed quickly by the CPU and I/O devices. The CPU fetches instructions and data directly from memory, making memory the only large storage medium directly accessible by the processor. Programs must be mapped to physical memory addresses and loaded before execution. When execution ends, memory is released for future use.

To ensure responsiveness and maximize CPU utilization, a computer must hold multiple programs in memory simultaneously, creating the need for sophisticated memory-management techniques. Different algorithms exist, each suited to particular hardware designs and requiring specific hardware support. The OS keeps track of which parts of memory are in use, allocates and deallocates memory as needed, and decides which processes or data should reside in memory at any given time. Memory-management strategies are covered in detail in Chapters 9 and 10.

File-System Management

To make storage convenient and uniform for users, the OS provides a logical view of information storage through files. A file is an abstract unit of related information, ranging from program binaries to text documents, images, and audio files. The OS maps files onto physical storage devices, each of which has its own characteristics such as access speed, capacity, and access patterns.

File systems often organize files into directories for ease of use, and access control is necessary when multiple users share data. The OS manages the creation, deletion, and manipulation of files and directories, maps files to storage, and handles backups on stable storage. These responsibilities are elaborated upon in Chapters 13 through 15.

Mass-Storage Management

Because main memory is volatile and limited in capacity, computer systems rely on secondary storage—typically HDDs or nonvolatile memory devices—to hold programs and data long-term. Programs are stored on disk until execution, and many applications use disks continuously during operation. As secondary storage performance heavily affects overall system speed, efficient management is crucial.

The OS handles disk-related tasks such as free-space management, disk scheduling, storage allocation, mounting and unmounting devices, partitioning, and protecting data from unauthorized access. Tertiary storage, including magnetic tape and optical media, is also used for backups and archival purposes. Though not essential for performance, tertiary storage may also be managed by the OS, performing tasks such as media mounting, allocation, and data migration. These concepts are explored in Chapter 11.

Cache Management

Caching is a key mechanism for improving system performance. Frequently accessed information is copied from slower storage (such as main memory or disk) into a faster, smaller storage area called a cache. When data is requested, the system first checks the cache; if the data is present, access is quick. Otherwise, the data is retrieved from the slower source and stored in the cache under the assumption that it will be needed again.

Caches exist at multiple levels, including hardware registers, CPU instruction caches, and data caches. The OS typically manages higher-level caches, such as disk buffers and page caches. Cache management is critical because caches are small and require intelligent replacement algorithms to maximize efficiency. In systems with multitasking or multiprocessing, ensuring that cached values remain consistent across processes or CPUs introduces problems such as cache coherence, typically enforced by hardware. Distributed systems further complicate consistency because multiple replicas of the same data may exist across machines, requiring synchronization techniques to maintain correctness.

I/O System Management

One purpose of the operating system is to abstract away the complexities of hardware devices from users and even from most of the OS itself. In UNIX-like systems, this abstraction is achieved through an I/O subsystem that includes buffering, caching, spooling components, a device-independent I/O interface, and device drivers for specific hardware. The I/O subsystem cooperates with interrupt handlers and device drivers to manage devices efficiently, perform data transfers, and detect I/O completion. Chapter 12 provides a deeper examination of these mechanisms and their integration with other parts of the operating system.

Security and Protection

In a computer system that supports multiple users and concurrent execution of processes, access to data and system resources must be carefully regulated. The operating system enforces rules ensuring that only authorized processes can operate on files, memory regions, CPU time, and other resources. Hardware mechanisms assist in this protection—for example, memory-addressing hardware confines each process to its own address space, the timer guarantees that no process can retain the CPU indefinitely, and device-control registers are kept inaccessible to user processes to protect the integrity of peripheral devices.

Protection refers to the set of mechanisms that control how processes or users access system resources. These mechanisms must provide a way to specify access rules and must reliably enforce them. Strong protection contributes to system reliability by detecting errors at subsystem interfaces early, preventing the spread of faults from one malfunctioning component to another. Without adequate protection, system resources are vulnerable to misuse by unauthorized or incompetent users. Protection systems therefore distinguish authorized usage from unauthorized usage, a topic explored further in Chapter 17.

Even with proper protection mechanisms in place, a system may still be vulnerable if it lacks adequate security. Protection controls how resources can be accessed, but security ensures that only legitimate users can access the system in the first place and that the system is defended from malicious attacks. If a user’s authentication credentials are stolen, an attacker can modify or delete data despite correct file and memory protections. Security mechanisms defend against threats such as viruses, worms, denial-of-service attacks, identity theft, and unauthorized use of system resources. Depending on the operating system, some security tasks are enforced directly by the OS, while others rely on administrative policy or additional software. With the rapid rise of security incidents, operating-system security has become a highly active area of research and implementation, discussed in Chapter 16.

To support protection and security, an operating system must reliably identify users. Most systems maintain a list of user names paired with numerical user identifiers (user IDs), called SIDs on Windows systems. When a user logs in, authentication determines the correct user ID, which is then associated with all of the user’s processes and threads. When needed, the user ID can be translated back into a human-readable user name.

Operating systems often need to distinguish not only among individual users but also among groups of users. For example, on UNIX, the owner of a file may have full access to it, while a designated group may be allowed only to read it. This requires defining group names and group identifiers, stored in system-wide group lists. A user may belong to multiple groups depending on system design, and the group IDs are recorded in all of the user’s processes and threads.

Although a user’s normal user ID and group ID generally determine their access rights, situations arise where a user must temporarily gain higher privileges—for example, to interact with a restricted device. Operating systems therefore support controlled privilege escalation. On UNIX systems, this is commonly achieved via the setuid attribute, which allows a program to run with the privileges of the file’s owner rather than the privileges of the user executing it. These elevated rights remain in effect until the program explicitly drops them or terminates.

Vitualization

Virtualization abstracts a single computer’s hardware into multiple isolated execution environments, allowing several operating systems to run simultaneously on the same physical machine. Each environment behaves like an independent computer, and users can switch among them much like switching between processes.

It differs from emulation: emulation translates instructions between different CPU architectures and is slower, while virtualization runs guest operating systems on the same native CPU architecture, making it far more efficient. Virtualization first appeared on IBM mainframes to support multiple users and later became popular on x86 systems through technologies like VMware, where a virtual machine manager (VMM or hypervisor) controls guests, allocates resources, and ensures isolation.

Today, virtualization is widely used on desktops to run multiple OSes and in data centers to host many virtual machines on the same hardware. Modern hypervisors often replace the host OS entirely, acting as the operating system for virtual machines. This textbook itself provides a Linux VM as an example of how virtualization enables consistent environments across different host systems

Distributed System

A distributed system consists of multiple physically separate computers—often heterogeneous—connected by a network so users can access shared resources seamlessly. Sharing resources across machines improves performance, functionality, reliability, and data availability. Some operating systems hide networking behind file-like interfaces (such as NFS), while others require explicit network operations (like FTP). The usefulness of a distributed system depends heavily on the networking protocols it uses.

Networking forms the foundation of distributed systems. A network is simply a communication path between systems, and networks vary by protocol, distance, and transmission media. TCP/IP is the dominant protocol and underlies the Internet, supported by nearly all modern operating systems. Networks can be categorized by scale: LANs connect systems within a building or campus; WANs span cities or countries; MANs connect buildings within a city; and PANs use technologies like Bluetooth or Wi-Fi for short-range communication between devices. Networking media range from copper wires and fiber optics to wireless and satellite links.

Operating systems support distributed computing to different degrees. A network operating system provides file sharing and message-passing between machines, but each system remains largely independent. A distributed operating system, in contrast, integrates multiple computers so closely that they appear to users as if they were a single unified system. This deeper level of coordination and transparency is explored further in Chapter 19

Kernel Data Structures

Operating systems rely heavily on efficient data structures to organize and manage information inside the kernel. While arrays allow direct access to fixed-size elements, they are unsuitable when item sizes vary or when frequent insertions and deletions are required. In such cases, linked lists become essential. A linked list stores elements in sequence, with each item pointing to the next; variants include singly linked lists, doubly linked lists, and circular lists. Although lists support flexible insertion and deletion, searching them is linear in the worst case. Lists often form the basis for higher-level structures, such as stacks and queues, both of which the kernel uses extensively. A stack follows the LIFO principle and is crucial for function calls, storing parameters and return addresses, while a queue follows FIFO semantics and appears frequently in scheduling tasks or I/O operations.

Trees offer a hierarchical way to represent data. A binary tree restricts each node to two children, and a binary search tree introduces ordering to enable efficient lookup. However, an unbalanced tree may degrade to linear-time performance, so many operating systems employ balanced trees—such as red–black trees—to ensure logarithmic access time. Linux uses red–black trees in its CPU scheduler.

Hash functions provide another mechanism for rapid data retrieval. By converting input data into numeric indices, a hash function can enable constant-time lookup. Collisions—different inputs producing the same hash value—are handled by chaining items together using linked lists at the same index. Hash maps build on this idea to associate key–value pairs, such as mapping user names to passwords.

Bitmaps are compact structures that use a string of bits to represent the state of many resources efficiently. Each bit corresponds to a resource and records its availability. Because they are extremely space-efficient, bitmaps are commonly used for tracking disk blocks and other large collections of resources.

Together, these fundamental structures—lists, stacks, queues, trees, hash maps, and bitmaps—form the backbone of kernel algorithms. They enable the operating system to manage memory, schedule processes, track resources, and maintain high performance.

Computing environments

Traditional computing environments have evolved significantly as networking and web technologies have matured. Earlier, office environments consisted of standalone PCs connected to internal networks with limited remote access and basic file or print servers. Today, high-bandwidth WANs and web-based portals enable seamless access to internal resources. Thin clients and mobile devices now supplement traditional desktops, synchronizing data and using wireless or cellular networks to reach corporate systems. Home networks have similarly advanced, with broadband connections enabling families to run small networks, share printers and servers, and use firewalls to protect against external threats.

Historically, computing distinguished between batch and interactive systems. As resources were scarce, time-sharing allowed multiple users to share a system by rapidly switching the CPU among processes. While classic time-sharing systems are rare today, the same scheduling principles apply to modern desktops and mobile devices, where multiple windows, browser tabs, and background services run concurrently.

Mobile computing represents a major shift, driven by smartphones and tablets that are lightweight and highly portable. Although these devices traditionally sacrificed performance and storage, modern mobile hardware now provides sophisticated features—such as GPS, gyroscopes, and accelerometers—that enable new application types, including navigation, motion-controlled games, and augmented reality. Despite this capability, mobile devices remain constrained by battery life, limited storage compared to PCs, and lower CPU power. Mobile platforms are dominated by Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android.

Client–server computing is a specialized form of distributed computing where clients request services and servers respond. Servers may act as compute servers, executing operations on behalf of clients, or as file servers, delivering files such as web pages or multimedia content. This model underpins most modern web and enterprise applications.

Peer-to-peer (P2P) computing removes the distinction between clients and servers; instead, all nodes act as peers that both request and offer services. P2P networks avoid server bottlenecks by distributing workload across many nodes. Service discovery may be centralized through a lookup server—as in Napster—or decentralized via broadcast queries, as used in Gnutella. Modern systems like Skype use hybrid approaches, combining centralized authentication with decentralized communication.

Cloud computing extends virtualization into large-scale, on-demand computing services. Clouds provide computing power, storage, and applications over the Internet. Deployment models include public, private, and hybrid clouds, and service models include SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS. Behind these services operate traditional operating systems, hypervisors, and cloud management tools such as VMware vCloud Director or Eucalyptus. Cloud architectures combine massive virtual machine clusters with firewalls, load balancers, and automated resource management.

Real-time embedded systems dominate everyday life, appearing in car engines, appliances, industrial robots, and consumer electronics. These systems often use specialized operating systems or even dedicated hardware to meet strict timing constraints. A real-time system must produce correct outputs within precise deadlines or risk failure—for example, in a robot arm, medical imaging device, or engine control unit. Embedded systems increasingly form connected networks, contributing to smart homes and intelligent devices that can autonomously manage environments.

Free and Open-source OS

The availability of free and open-source operating systems has greatly simplified the study and development of operating systems. Both provide source code rather than only compiled binaries, but the terms free software and open source represent different philosophies. Free software, championed by the Free Software Foundation, guarantees users four freedoms: to run, study, modify, and redistribute programs. Open-source software simply makes source code available and does not always guarantee these freedoms. As a result, all free software is open source, but not all open-source software is free. GNU/Linux is the most prominent example of a system developed under these principles, whereas Microsoft Windows remains proprietary, and macOS uses a hybrid model with an open-source Darwin kernel and closed-source components.

Having access to source code makes it possible for programmers and students to compile, modify, and experiment with operating-system internals—something difficult to achieve through reverse engineering of binaries. Open-source systems encourage broad community involvement in writing, debugging, and improving code. Advocates argue that this model increases reliability and security because more people examine and test the code. Commercial vendors increasingly support open-source development, earning revenue through services, support, and hardware rather than software licensing.

Historically, software was commonly distributed with source code. Early computing communities, such as MIT’s hackers and DECUS members, routinely shared programs openly. By the 1980s, however, companies restricted software distribution and released only binaries to protect intellectual property. In response, Richard Stallman launched the GNU project in 1984 to create a free UNIX-like operating system and introduced the GNU General Public License (GPL), a “copyleft” license requiring that redistributed software preserve user freedoms.

GNU ultimately lacked a working kernel, but in 1991 Linus Torvalds released a UNIX-like kernel—Linux—using GNU tools. Rapid global collaboration, enabled by the Internet, quickly matured the system. When Torvalds relicensed Linux under the GPL, it became fully free software. Today, GNU/Linux exists in many distributions such as Red Hat, Debian, Ubuntu, and Slackware, varying in purpose and features. Virtualization tools like VirtualBox and QEMU allow users to run Linux and other systems easily for learning and experimentation.

BSD UNIX has a parallel open-source history. Originating from AT&T UNIX at Berkeley, BSD was initially restricted by licensing issues but eventually became fully open with the release of 4.4BSD-Lite in 1994. Modern BSD variants include FreeBSD, NetBSD, OpenBSD, and DragonflyBSD. Their source code is easily accessible and maintained through modern version-control systems like Subversion and Git. Apple’s macOS incorporates an open-source BSD-based kernel named Darwin, also publicly available.

Solaris represents another lineage. Originally based on BSD and later System V UNIX, Solaris was partially open-sourced as OpenSolaris before Oracle’s acquisition of Sun. Successor projects like Illumos continue its open-source development.

The rise of open-source systems has transformed operating-system education. Students can examine real kernels, modify them, run them in virtual machines, and explore historical systems through simulators. The diversity of open-source projects fosters innovation, cross-pollination of ideas, and widespread adoption. With modern tools and open access to source code, transitioning from learning operating systems to contributing to their development has become more accessible than ever.

Q&A

Further Readings