Moral Dilemma

Is Morality Unified Enough to Be Defined?

No, morality is not unified enough to admit a single, simple, non-controversial definition.

- Moral systems differ across cultures, across individuals, and across philosophical theories.

- Some moral rules prioritize fairness and harm prevention, while others prioritize loyalty, purity, authority, or obedience.

Because of this variation, there is no single feature that captures all moral judgments across societies.

v1: Most of these moral rules operate as unconscious habits learned through culture, upbringing, religion, and social practice. People usually follow them automatically, without explicit reflection or justification.

v2: Morality is the informal public system that, given that they were reasonable and looking for an unforced general agreement, would not be rejected by any rational people.

Two Ways to Understand Morality

Morality can be broadly divided into two forms:

1. Descriptive Morality

Descriptive morality refers to the moral beliefs, principles, rules, values, and practices that people in fact accept and use to guide behavior, whether consciously or unconsciously.

- It describes how people actually behave morally.

- It makes no claim about justification, correctness, or truth.

- It varies widely across societies and individuals.

Descriptive morality belongs to the domain of psychology, sociology, anthropology, and history.

2. Normative Morality

Normative morality refers to a system of principles or rules of conduct that ought to govern the behavior of rational agents, and which can be justified by reasons.

- It is evaluative, not descriptive.

- It asks whether a moral code should be accepted.

- It requires public justification and reasoning.

Normative morality belongs to moral philosophy and ethics.

Ethics, Morality, and Law

These three are related but distinct:

- Morality: the system of norms and values guiding judgments of right and wrong based on some shared beliefs.

- Ethics: the reflective and critical examination of moral systems.

- Law: a formal system of rules enforced by institutions.

A legal action may be immoral, and a moral action may be illegal. Ethics exists to evaluate morality, not merely follow it.

Morality in a Globalized World

Globalization has fundamentally changed the moral landscape.

People from different cultures, religions, and moral backgrounds now:

- Work together

- Live together

- Compete and cooperate within the same systems

As a result:

- Shared moral assumptions can no longer be taken for granted.

- Moral conflict arises even when no laws are broken.

- Many disagreements are not about right versus wrong, but about different moral priorities.

How Should We Deal with Moral Diversity?

In a plural and globalized society, the solution is not to abandon morality, nor to impose one moral system on everyone.

Instead, morality must shift from thick cultural codes to thin public principles.

This means:

- Privately, individuals may hold strong moral intuitions shaped by culture.

-

Publicly, expectations should be limited to rules that can be justified to people who do not share the same background.

- Preventing harm

- Respecting concent

- Avoiding coercion and deception

- Allowing disagreement without moral condemnation

This approach does not eliminate conflict entirely, but it significantly reduces moral friction in pluralistic settings. However, it is not risk-free: an excessive focus on harm prevention can itself be misused to justify coercive, paternalistic, or unethical practices.

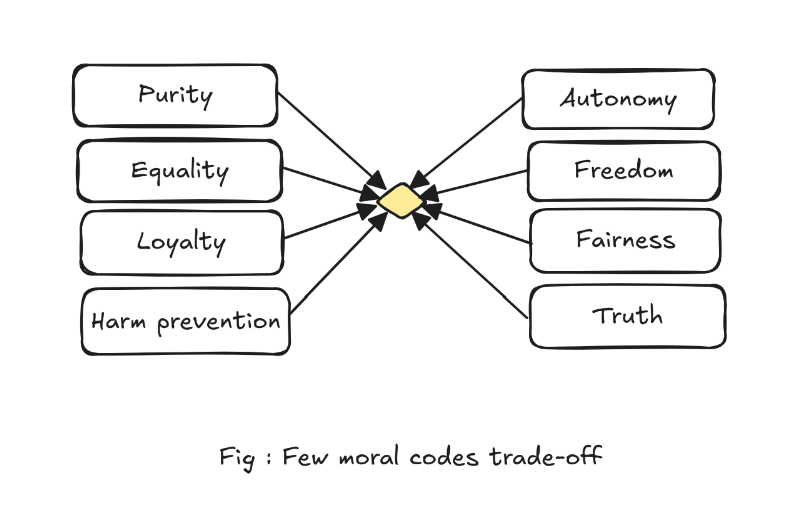

Typical High-Conflict Pairs

- Freedom vs Safety

- Justice vs Mercy

- Loyalty vs Fairness

- Authority vs Conscience

- Purity vs Autonomy

- Truth vs Harm Prevention

- Individual Rights vs Collective Good